How Did the European Starling Get to America? The Full Origin Story Explained

If you’ve ever seen a flock of dark, speckled birds swirling through the sky in mesmerizing patterns, you’ve probably spotted European starlings. But here’s something that might surprise you: these birds aren’t native to North America at all. So, how did the European starling get to America? The answer involves a wealthy New York businessman, a questionable plan to import European wildlife, and one of the most dramatic biological invasions in modern history.

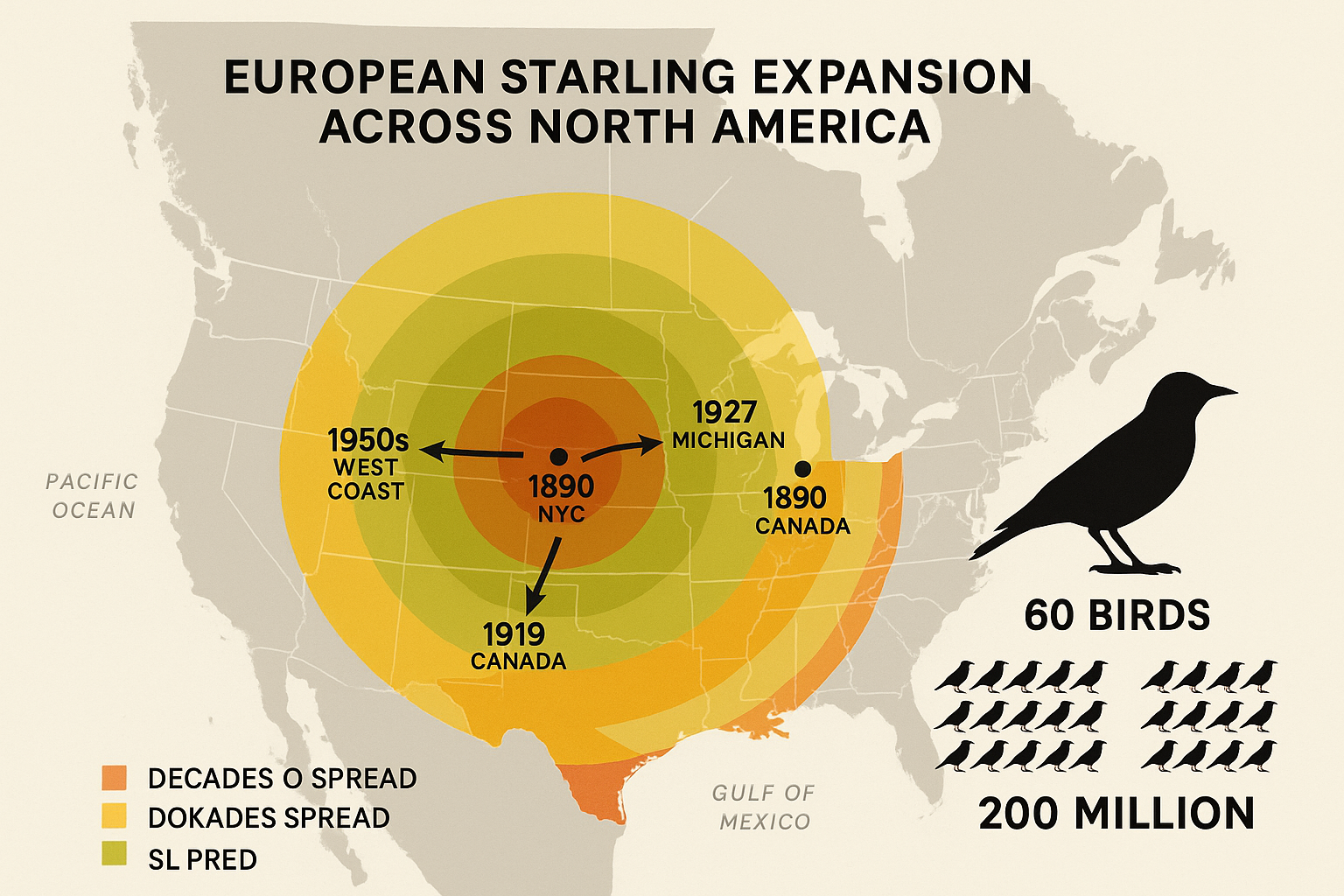

In 1890, a man named Eugene Schieffelin released 60 European starlings in Central Park, New York City. He followed up with 40 more birds in 1891. Those 100 birds became the ancestors of over 200 million starlings now living across the United States and Canada. This article breaks down the full story who released them, why they did it, how the birds spread so fast, and what impact they’ve had on native wildlife.

Key Takeaways

- Eugene Schieffelin released 60 European starlings in Central Park in 1890, followed by 40 more in 1891, establishing the first successful breeding population in North America.

- The Shakespeare myth is false there’s no evidence Schieffelin wanted to introduce all birds mentioned in Shakespeare’s works; this story was created in 1948 without factual support.

- Starlings spread gradually at first, taking 37 years to reach the southern U.S., but eventually colonized the entire continent with a population now exceeding 200 million birds.

- European starlings are classified as invasive because they compete aggressively with native cavity-nesting birds like bluebirds and woodpeckers for nesting sites.

- Earlier introduction attempts failed starlings were released in Pennsylvania (1850) and Ohio (1872-1873) but didn’t establish permanent populations until Schieffelin’s release.

What Is the European Starling?

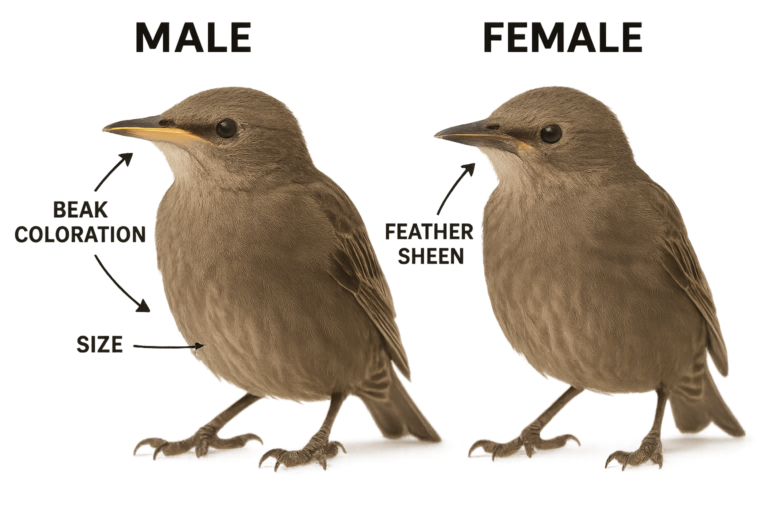

The European starling (Sturnus vulgaris) is a medium-sized songbird native to Europe, western Asia, and North Africa. These birds measure about 8.5 inches in length with a 15-inch wingspan[1]. They’re stocky, short-tailed birds with pointed beaks that turn bright yellow during breeding season.

In their natural habitat across Europe, starlings are admired for their intelligence and vocal abilities. They can mimic the sounds of other birds, car alarms, and even human speech. Their glossy black feathers show iridescent green and purple hues in sunlight, and in winter, they develop distinctive white speckles across their bodies.

Physical traits that helped them thrive in America:

- Strong, adaptable beaks for eating insects, seeds, and fruit

- Cavity-nesting behavior (they nest in holes in trees or buildings)

- Highly social nature they form massive flocks

- Aggressive territorial behavior during breeding season

- Year-round activity (they don’t hibernate)

In the 1800s, many Americans viewed European wildlife as more “refined” than native species. Victorian-era naturalists often tried to bring European plants and animals to North America, believing they would improve the landscape. The European starling fit perfectly into this misguided vision.

If you’re interested in learning more about starlings and their behavior, these birds have become one of the most studied invasive species in North America.

How Did the European Starling Get to America?

The Shakespeare Enthusiasts Behind the Introduction

The story of how the European starling got to America starts with the American Acclimatization Society, founded in New York City in the 1870s. This organization had one main goal: introduce European plants and animals to North America.

Members believed that bringing European species to America would:

- Make the landscape more beautiful

- Provide economic benefits (some birds ate crop pests)

- Create cultural connections to Europe

- “Improve” what they saw as an incomplete American ecosystem

Eugene Schieffelin became chairman of the American Acclimatization Society in 1877[2]. Under his leadership, the group attempted to introduce dozens of European bird species to New York, including bullfinches, chaffinches, nightingales, and skylarks. Most of these attempts failed the birds either died quickly or couldn’t establish breeding populations.

The starling was different.

Eugene Schieffelin — The Man Who Released the Starlings

Eugene Schieffelin was a wealthy pharmaceutical manufacturer who lived in New York City. He had the money, the connections, and the determination to import European birds and release them in American cities.

What we know about Schieffelin:

- Chairman of the American Acclimatization Society starting in 1877

- Made multiple attempts to introduce European bird species

- Successfully introduced European starlings in 1890-1891

- Also tried (and failed) to introduce nightingales, skylarks, and other species

Here’s where the story gets interesting. You’ve probably heard that Schieffelin wanted to introduce every bird mentioned in Shakespeare’s plays to America. This is one of the most repeated “facts” about the European starling introduction.

But it’s not true.

The Shakespeare story was created by naturalist Edwin Way Teale in 1948-58 years after the starling release without any evidence to support it. Researchers have found no historical documents, letters, or records showing Schieffelin ever mentioned Shakespeare as his motivation.

The real reasons were likely simpler:

- Belief that European birds would control insect pests

- Desire to make American cities feel more like European ones

- General Victorian-era enthusiasm for “acclimatization” projects

Why the European starling became the most common bird in America helps explain why Schieffelin’s introduction had such lasting impact.

The 1890–1891 Release in Central Park

On a cold day in March 1890, Eugene Schieffelin released 60 European starlings in Central Park, New York City[1]. The birds were imported from Europe specifically for this purpose.

The results weren’t immediately dramatic. Some birds died. Others disappeared. But enough survived to breed.

In 1891, Schieffelin released 40 more starlings in Central Park. This second release helped strengthen the population. By 1896 just six years later starlings were firmly established in the New York area[1].

Important context: Schieffelin wasn’t the first to try this.

- 1850: Starlings were released in West Chester, Pennsylvania (failed)[2]

- 1872-1873: Starlings were released in Cincinnati, Ohio (failed)[2]

- 1876: Wild starlings were captured in Massachusetts (suggesting earlier unknown releases)[2]

- 1884: Wild starlings were captured in New Jersey

These earlier attempts didn’t create permanent populations. Schieffelin’s 1890-1891 releases succeeded where others failed, possibly because:

- He released birds in two consecutive years

- Central Park provided ideal habitat

- The timing coincided with favorable weather

- The population reached a critical mass for breeding

Why Were European Starlings Brought to America?

The motivations behind introducing European starlings reflect the ecological attitudes of the late 1800s a time when people believed humans could and should “improve” nature.

Primary reasons for the introduction:

Cultural nostalgia – Many American Acclimatization Society members were European immigrants or descendants who wanted familiar species from their homelands.

Pest control – Starlings eat insects, and some people believed they would help control agricultural pests. (This turned out to be only partially true.)

Victorian “improvement” ideology – The late 1800s saw widespread belief that European species were superior and would enhance American ecosystems.

The American Acclimatization Society wasn’t unique. Similar groups existed across the United States, all working to introduce non-native species. These organizations operated before modern ecological science understood the dangers of invasive species.

What they didn’t understand:

- How quickly introduced species could spread

- The competitive disadvantage to native birds

- The long-term ecological consequences

- The difficulty of removing established populations

By the time scientists recognized these problems, it was far too late. The starlings had already begun their continent-wide expansion.

How the European Starling Spread Across America

Rapid Reproduction

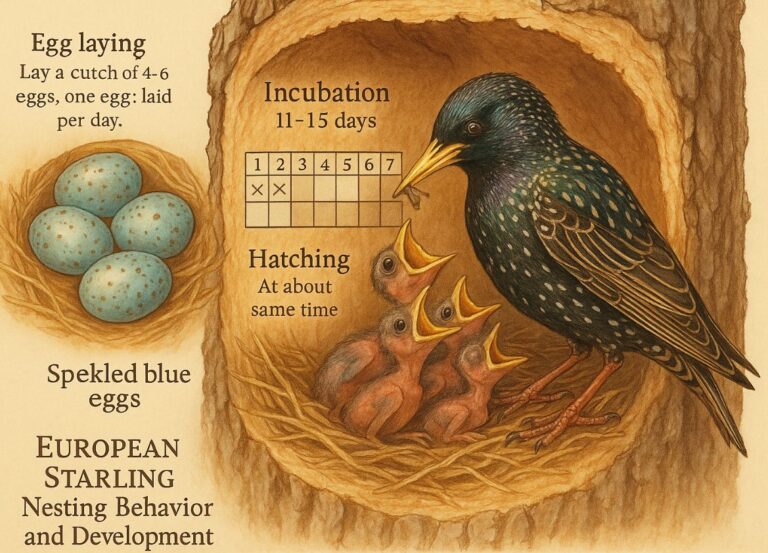

European starlings are cavity-nesting birds, meaning they build nests inside holes in trees, buildings, or other structures. This gives them a huge advantage in both natural and urban environments.

Reproductive facts:

- Females lay 4-6 eggs per clutch

- Can raise 2-3 broods per year

- Eggs hatch in about 12 days

- Young birds leave the nest after 21 days

- Starlings can breed in their first year

This reproductive rate allowed populations to grow exponentially. A single pair of starlings can produce 12-18 offspring in one breeding season, and those offspring can breed the following year.

Adaptability to Cities, Farms, and Forests

Unlike many bird species that require specific habitats, European starlings thrive almost anywhere. This adaptability is key to understanding how they spread so quickly.

Habitats where starlings succeed:

Urban areas – Buildings provide nesting cavities; human food waste provides meals

Agricultural land – Farms offer insects, grain, and livestock feed

Suburban neighborhoods – Lawns, gardens, and ornamental trees create perfect foraging grounds

Forests and woodlands – Natural tree cavities provide nesting sites

Grasslands and prairies – Open areas allow ground-feeding behavior

This flexibility meant starlings could colonize diverse ecosystems as they spread westward from New York.

Expansion Timeline

The spread of European starlings across North America was gradual at first, then explosive.

Year-by-year breakdown:

| Year | Geographic Range | Key Milestone |

|---|---|---|

| 1890 | Central Park, NYC | Initial release of 60 birds[1] |

| 1891 | Central Park, NYC | Second release of 40 birds[1] |

| 1896 | New York area | Firmly established breeding population[1] |

| 1900 | Ossining, NY; parts of CT and NJ | Limited expansion from NYC[2] |

| 1910 | Philadelphia area | Breeding populations in Pennsylvania[2] |

| 1919 | Brockville, Ontario | First confirmed Canadian population[2] |

| 1927 | Michigan, Indiana, Kentucky, Tennessee, Georgia, South Carolina | Major southern expansion—37 years after release[2] |

| 1927 | Quebec City area | Established in eastern Canada[2] |

| 1942 | California | Reached the West Coast |

| 1950s-1960s | Pacific Northwest, Alaska | Continent-wide distribution |

| 2025 | All of North America | 200+ million birds |

The expansion took 37 years to reach the southern United States from the initial 1890 release[2]. But once populations reached critical mass in multiple regions, the spread accelerated dramatically.

For more context on where the European starling becomes a problem, their adaptability has made them successful in nearly every North American ecosystem.

Ecological Impact of European Starlings in the U.S.

Competition With Native Birds

The biggest ecological problem with European starlings is their aggressive competition for nesting cavities. Because they’re cavity nesters, they directly compete with native birds that use the same nesting sites.

Native species harmed by starling competition:

Eastern Bluebirds – Starlings take over bluebird nest boxes and destroy eggs

Red-headed Woodpeckers – Starlings steal cavities that woodpeckers excavate

Purple Martins – Starlings occupy martin houses meant for these native birds

Tree Swallows -Lose nesting sites to aggressive starlings

American Kestrels – Small falcons that need cavities for nesting

Starlings don’t just occupy empty cavities they actively evict other birds, destroy eggs, and kill nestlings. This aggressive behavior has contributed to population declines in several native cavity-nesting species.

If you’re dealing with starlings at your feeders, check out this guide on how to get rid of starlings at bird feeders.

Agricultural Impact

European starlings cause significant economic damage to agriculture across North America.

Negative agricultural impacts:

Crop damage -Starlings eat fruit (cherries, grapes, berries), grain (corn, wheat), and vegetables

Livestock feed consumption – Flocks gather at feedlots and consume cattle feed

Economic losses – Estimated at tens of millions of dollars annually

Disease transmission – Large flocks can spread diseases to livestock

One positive: insect consumption

Starlings do eat insects, including some agricultural pests like beetles, caterpillars, and grasshoppers. During breeding season, they feed their young almost exclusively on insects. However, this benefit doesn’t outweigh the damage they cause.

Benefits? (Very Few)

It’s worth being honest: European starlings provide very few ecological benefits in North America.

Minor positive aspects:

- Insect pest consumption during breeding season

- Aeration of soil through ground-feeding behavior

- Cultural significance (murmurations are visually stunning)

- Research value for studying invasive species

These limited benefits don’t justify their introduction, and they don’t offset the harm to native bird populations and agriculture.

Are European Starlings Considered Invasive?

Yes. European starlings are classified as an invasive species in North America.

An invasive species is one that:

- Is non-native to the ecosystem

- Causes economic or environmental harm

- Spreads rapidly without natural predators or controls

Starlings check all three boxes.

Legal status:

- Not protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act — Unlike most bird species, starlings can be legally controlled or removed

- Classified as an invasive species by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

- No hunting license required in most states to remove them from property

- Considered an agricultural pest in many jurisdictions

Because they’re invasive, property owners can legally remove starlings, destroy nests, and prevent them from nesting in structures. This is different from native birds, which are protected by federal law.

For more information about the difference between starlings and native blackbirds, understanding identification helps with proper bird management.

Interesting Facts About European Starlings

Despite their invasive status, European starlings are genuinely fascinating birds.

Murmurations

Murmurations are the spectacular aerial displays where thousands of starlings fly together in coordinated, swirling patterns. These formations happen most often at dusk during fall and winter.

Why they do it:

- Protection from predators (hawks have trouble targeting individual birds)

- Warmth (flocking together conserves heat)

- Information sharing (birds communicate about food sources)

- Social bonding

Murmurations can include hundreds of thousands of birds moving as a single organism. The patterns emerge from simple rules each bird follows about spacing and direction.

Vocal Mimicry

European starlings are exceptional vocal mimics. They can imitate:

- Other bird species’ songs and calls

- Car alarms and mechanical sounds

- Human speech and whistles

- Musical instruments

Males use mimicry to attract mates—the more sounds a male can produce, the more attractive he is to females. Some starlings have been recorded producing over 20 different sounds.

For more on bird vocalizations, explore why birds sing in the morning.

Intelligence

Starlings are highly intelligent birds. Research shows they can:

- Recognize individual human faces

- Use tools to access food

- Learn through observation

- Solve multi-step problems

- Understand basic grammatical patterns (in laboratory studies)

This intelligence contributes to their success as an invasive species—they quickly learn to exploit new food sources and avoid threats.

Lifespan

In the wild, European starlings typically live 2-3 years. However, the oldest recorded starling lived over 15 years[1]. High mortality in the first year keeps the average lifespan low, but birds that survive to adulthood can live much longer.

Global Population Size

The North American population of European starlings is estimated at over 200 million birds. This makes them one of the most abundant bird species on the continent—all descended from the 100 birds released in Central Park between 1890 and 1891.

FAQs

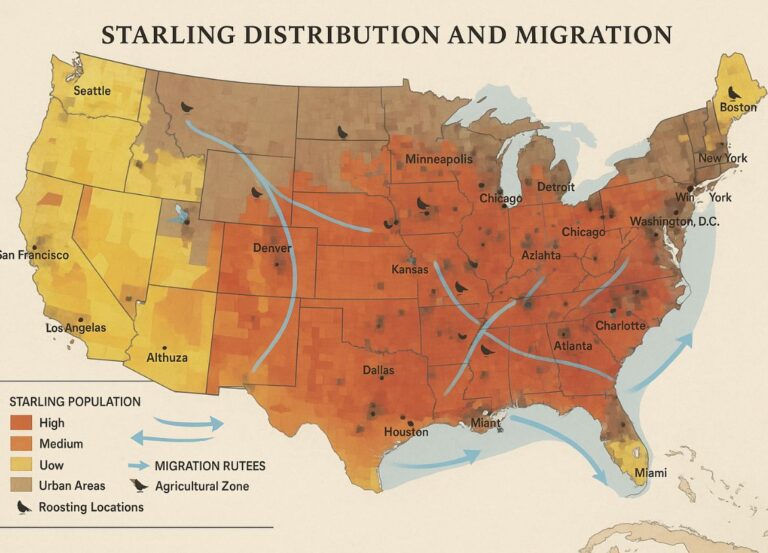

Do European starlings migrate?

Partially. European starlings in North America show partial migration patterns. Northern populations migrate south for winter, while southern populations stay year-round. Birds from Canada and the northern U.S. move to warmer areas, but many starlings in temperate regions remain in the same area throughout the year.

How many European starlings are in America today?

Current estimates place the North American starling population at over 200 million birds. This represents one of the most successful biological invasions in history, with all birds descended from approximately 100 individuals released in New York between 1890 and 1891.

Are starlings harmful to native birds?

Yes. European starlings compete aggressively with native cavity-nesting birds for nesting sites. They evict other birds, destroy eggs, and kill nestlings. Species like Eastern Bluebirds, Purple Martins, and Red-headed Woodpeckers have experienced population declines partly due to starling competition.

If you’re trying to identify young starlings, this guide on how to tell if a baby starling is male or female provides helpful information.

Why do starlings make murmuration’s?

Starlings form murmuration’s for protection from predators, warmth, and social communication. The coordinated flight patterns make it difficult for hawks and other predators to target individual birds. Flocking also allows birds to share information about food sources and roosting sites.

Can you legally remove starlings from your property?

Yes. Because European starlings are not protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, property owners can legally remove them, destroy nests, and prevent nesting without permits in most areas. However, always check local regulations, as some municipalities have specific rules about wildlife control methods.

Conclusion

So, how did the European starling get to America? The answer is straightforward: Eugene Schieffelin, chairman of the American Acclimatization Society, released 60 starlings in Central Park in 1890, followed by 40 more in 1891. Those 100 birds established the first successful breeding population, which gradually spread across the continent over the next several decades.

Key points to remember:

The Shakespeare myth is false there’s no evidence Schieffelin wanted to introduce all birds from Shakespeare’s works

Earlier attempts to introduce starlings in 1850 and 1872-1873 failed to establish populations

Starlings spread gradually at first, taking 37 years to reach the southern U.S., but eventually colonized all of North America

The current population exceeds 200 million birds—all descended from Schieffelin’s releases

Starlings are classified as invasive and cause significant harm to native cavity-nesting birds and agriculture

The European starling introduction stands as a cautionary tale about the unintended consequences of human interference with ecosystems. What seemed like a harmless cultural project in 1890 became one of the most dramatic biological invasions in modern history.

Actionable next steps:

- Learn to identify European starlings and distinguish them from native species

- Support native bird populations by providing appropriate nest boxes

- Consider starling-resistant bird feeders if they’re causing problems in your yard

- Explore local bird conservation efforts in your area

For more bird-related content and guides, visit the Bird Talk Daily blog to expand your knowledge about backyard birds and conservation.