If you’ve ever sat on your patio in New Mexico and watched a colorful bird land on your fence, you already know the magic of backyard birding in the Land of New Mexico. Backyard Birds In New Mexico offer an incredible mix of desert specialists, mountain dwellers, and migratory visitors that you won’t find anywhere else in the country. From the cheerful songs of House Finches to the distinctive calls of Curve-Billed Thrashers, New Mexico’s unique geography creates a birdwatcher’s paradise right outside your window.

New Mexico sits at the crossroads of multiple ecosystems high desert, grasslands, mountain forests, and riparian corridors which means your backyard can attract an amazing variety of species throughout the year. Whether you live in Albuquerque, Santa Fe, Las Cruces, or a small town tucked into the mountains, understanding which birds visit your area and how to attract them will transform your outdoor space into a thriving wildlife habitat.

In this guide, I’ll walk you through the most common species you’ll see, how to identify them quickly, what they eat, and the best ways to make your yard irresistible to feathered friends. You’ll also learn about seasonal visitors, regional differences across the state, and simple conservation steps that make a real difference.

Key Takeaways

- New Mexico hosts over 550 bird species, with 30-40 common backyard visitors depending on your region and elevation

- Desert-adapted birds like Curve Billed Thrashers and Cactus Wrens thrive in New Mexico’s arid climate

- Water sources are critical providing fresh water can attract more birds than feeders alone in dry climates

- Seasonal migration brings dramatic changes, with different species appearing in winter versus summer months

- Native plants and proper feeders tailored to New Mexico’s climate will maximize bird activity year-round

Why New Mexico Is a Birdwatcher’s Paradise

New Mexico offers something special that most states can’t match extreme habitat diversity packed into one place. Within a few hours’ drive, you can go from Chihuahuan Desert scrubland at 3,000 feet to alpine forests above 13,000 feet. This creates ecological zones that support completely different bird communities.

The Rio Grande corridor acts as a major migration highway, funneling thousands of birds through the state each spring and fall. Bosque habitats those cottonwood forests along waterways become rest stops for exhausted travelers heading north or south. Your backyard might sit along this natural superhighway.

Year-round residents have adapted to New Mexico’s challenges: intense sun, limited water, temperature swings, and sparse vegetation in many areas. These tough birds have developed fascinating behaviors and physical traits that make them perfect subjects for observation.

The state’s low humidity and clear skies mean you can often see birds more clearly than in humid regions where haze obscures details. Morning light in New Mexico is legendary among photographers for good reason it makes bird colors pop brilliantly.

Many southwestern specialty birds reach the northern edge of their range in New Mexico, making the state a bucket-list destination for serious birders. But you don’t need to travel to remote locations many of these special species happily visit suburban feeders.

Common Backyard Birds In New Mexico

Let me break down the species you’re most likely to see in your New Mexico yard. I’ve organized these by how frequently they appear at feeders and water sources across the state.

House Finch

Appearance: Males sport a bright red head, chest, and rump with brown-streaked sides. Females are plain brown with heavy streaking and no red coloring. Both sexes have short, conical beaks perfect for cracking seeds.

Behavior: House Finches are social birds that travel in flocks, especially outside breeding season. They sing cheerful, warbling songs from high perches and aren’t shy about feeders. Males often sing while perched on power lines or roof edges.

Call description-A long, jumbled warbling song that sounds musical and energetic. Their call note is a simple “cheep” often given in flight.

Preferred food- Black oil sunflower seeds, nyjer (thistle), and millet. They’ll also eat fruit and visit hummingbird feeders occasionally.

Mourning Dove

Identification tips- soft tan-gray body with a long, pointed tail edged in white. Small head with black spots on the wings. Their flight creates a distinctive whistling sound from their wing feathers.

Feeding habits- Ground feeders that prefer eating seeds scattered below feeders rather than perching on them. They eat massive quantities their crops can hold over 17,000 seeds at once.

Where to spot them in NM- Literally everywhere. Mourning Doves thrive from desert valleys to mountain towns. They’re often seen on power lines and fence posts, and their mournful “coo-OOO-oo-oo” call is a soundtrack of New Mexico mornings.

White-Winged Dove

Why common in New Mexico: Originally a summer visitor, White-Winged Doves have expanded their range and now stay year-round in many New Mexico cities. They love urban and suburban areas with large trees.

Difference from Mourning Dove: Stockier build with a shorter, rounded tail. The key field mark is the bold white wing stripe visible in flight and sometimes when perched. Their call is a distinctive “who-cooks-for-you” that sounds almost owl-like.

Curve-Billed Thrasher

Signature traits: This is a true New Mexico specialty. Medium-sized bird with mottled gray-brown plumage and a long, downward-curved bill that’s perfect for digging in soil. Bright orange eyes stand out against the gray face.

Desert adaptation: That curved bill isn’t just for show—it’s a specialized tool for flipping rocks and probing cactus bases for insects. These birds thrive in desert scrub and often build nests in cholla cactus for protection from predators.

They give a loud “whit-WHEET!” call that’s one of the most recognizable sounds of the Southwestern desert. Once you learn it, you’ll hear them everywhere.

Northern Mockingbird

Songs and mimicry: Mockingbirds are the virtuosos of the bird world. A single male can learn over 200 different song types, including car alarms, other bird species, and even cell phone ringtones. They often sing at night, especially during breeding season.

Territorial behavior: These birds are fearless defenders of their space. They’ll dive-bomb cats, dogs, and even humans who get too close to their nests. Gray overall with white wing patches visible in flight and a long tail they often pump up and down.

Lesser Goldfinch

Small, energetic finches with bright yellow underparts. Males have black caps and backs (in New Mexico) while females are olive-green. They love nyjer seed and often hang upside-down while feeding.

Their tinkling, musical calls and flight songs add a cheerful soundtrack to any yard. They’re particularly common near water sources and often travel in small flocks.

Black-Chinned Hummingbird

The most common hummingbird in New Mexico backyards. Males have a black chin with a thin purple band (visible only in good light). Females are plain greenish above with white underparts.

They arrive in April and stay through September, visiting red and orange flowers plus hummingbird feeders. Their wings make a distinctive buzzing sound in flight.

Canyon Towhee

A large, chunky sparrow-like bird with plain brown plumage and a rusty cap. They have a distinctive rufous patch under the tail and a central breast spot. Canyon Towhees are ground feeders that scratch in leaf litter with both feet simultaneously.

Common in yards with natural landscaping and brush piles. Their call is a sharp “chili-chili-chili” that accelerates.

Western Scrub-Jay

Bold, intelligent, and beautiful. Bright blue head, wings, and tail contrast with gray-brown back and white throat with a blue necklace. These jays are highly vocal with harsh, scolding calls.

They cache food obsessively, hiding seeds and nuts for later. A single jay can hide thousands of items and remember most locations. They love peanuts and will become quite tame around feeders.

Gambel’s Quail

The iconic desert quail with a teardrop-shaped head plume. Males have a black face and rusty cap, while females are plainer. They travel in groups called coveys, often running across yards in single file.

Ground feeders that prefer scattered millet and cracked corn. Their “chi-CA-go-go” call is a classic sound of New Mexico mornings.

Bewick’s Wren

Small, energetic bird with a long tail often held upright. Bold white eyebrow stripe and barred tail. They sing complex, variable songs and investigate every crevice looking for insects.

Common around buildings, woodpiles, and brush. They’ll use nest boxes readily and are beneficial for controlling insect populations.

Spotted Towhee

Larger than sparrows with a black head and back (males), rufous sides, and white belly with white spots on the wings and back. Females are brown where males are black.

They scratch noisily in leaf litter under bushes, jumping forward and backward with both feet. Their call is a buzzy “drink-your-tea!”

Seasonal Backyard Birds in New Mexico

New Mexico’s bird populations shift dramatically with the seasons. Understanding these patterns helps you know what to expect and when to watch for special visitors.

Winter birds (November-March) include:

- Dark-Eyed Juncos arrive from mountain breeding areas

- White-Crowned Sparrows visit feeders in flocks

- American Robins gather in large groups eating berries

- Pine Siskins appear during irruption years

- Red-Breasted Nuthatches descend from high elevations

Summer residents (April-September) bring:

- Black-Chinned Hummingbirds at feeders

- Western Tanagers in mountain areas

- Blue Grosbeaks in riparian zones

- Lesser Nighthawks hunting insects at dusk

- Scott’s Orioles in desert regions

Spring and fall migrants pass through briefly:

- Warblers of many species (April-May, August-September)

- Flycatchers heading to breeding grounds

- Swallows moving in large flocks

- Shorebirds near water features

- Raptors along mountain ridges

| Season | Temperature Range | Key Bird Activity | Top Species to Watch |

|---|---|---|---|

| Winter | 20-50°F | Seed feeders busiest; mountain birds descend | Dark-Eyed Junco, White-Crowned Sparrow, Pine Siskin |

| Spring | 40-75°F | Migration peak; nesting begins | Hummingbirds, warblers, orioles arriving |

| Summer | 60-95°F | Breeding activity; fledglings appear | Black-Chinned Hummingbird, Western Tanager, young birds |

| Fall | 45-70°F | Second migration wave; birds fattening up | Southbound warblers, sparrow flocks forming |

The monsoon season (July-August) changes bird behavior dramatically. Increased moisture brings insect hatches that attract flycatchers and swallows. Rain fills natural water sources, sometimes reducing feeder activity temporarily.

Elevation matters tremendously in New Mexico. A yard at 7,000 feet in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains will see completely different seasonal patterns than a yard at 3,500 feet in the Rio Grande Valley, even though they’re only 50 miles apart.

How to Attract Backyard Birds in New Mexico

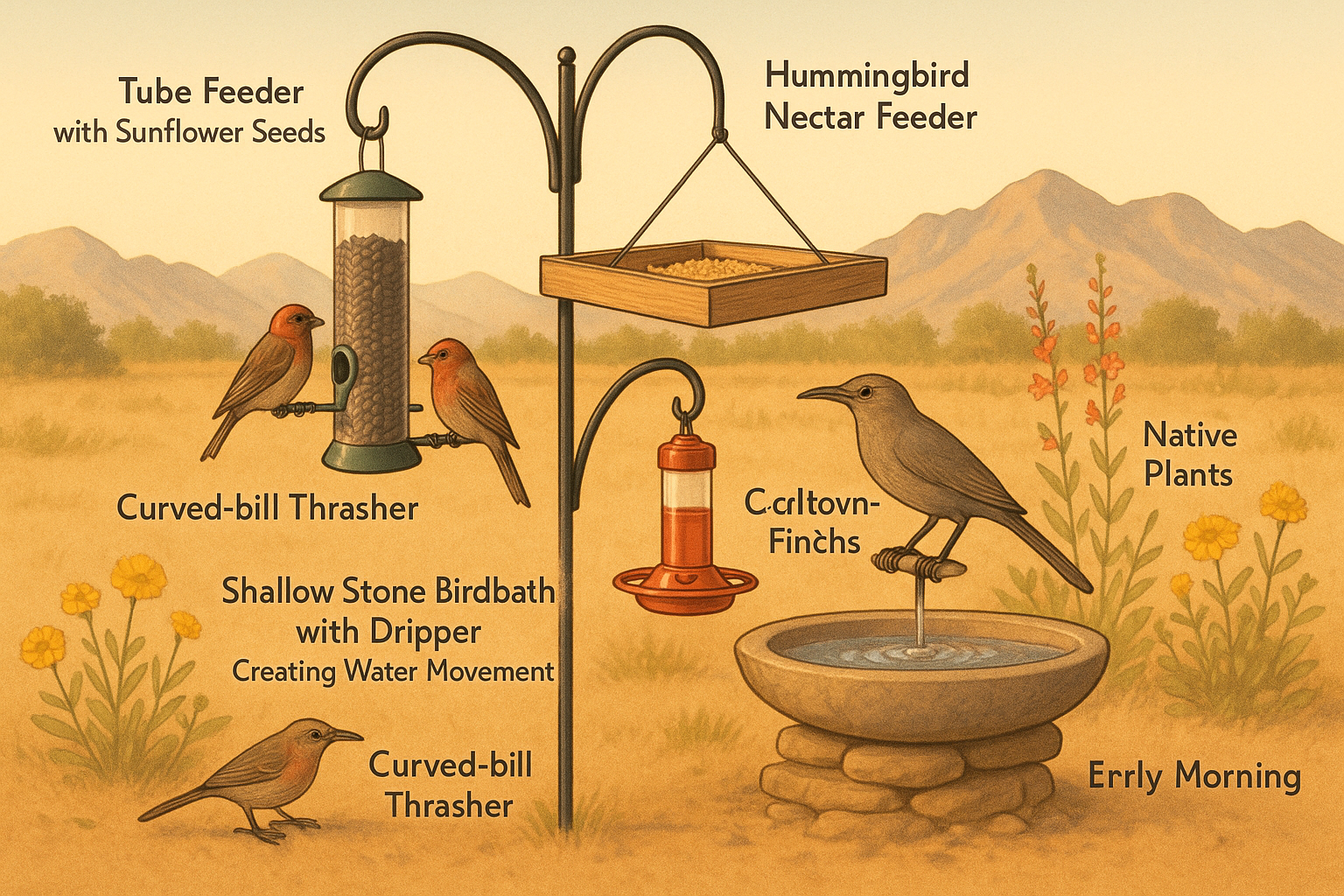

Making your New Mexico yard bird-friendly requires understanding the state’s unique challenges primarily water scarcity and intense sun. Here’s what works based on real-world results.

Best Bird Feeders for Desert Climates

Tube feeders with metal ports hold up better than plastic in intense UV radiation. Look for UV-resistant materials that won’t crack after a summer of New Mexico sun.

Platform feeders work excellently for ground-feeding species like doves, towhees, and quail. Choose designs with drainage holes since monsoon rains can soak seeds quickly.

Hummingbird feeders should have shade covers or be placed in areas that get afternoon shade. Direct sun heats nectar and promotes bacterial growth. Clean them every 2-3 days in summer heat.

Suet feeders need special consideration. Regular suet melts in summer temperatures above 80°F. Use no-melt suet cakes or only offer suet from October through April.

Hopper feeders protect seeds from weather but can trap heat. Choose lighter colors that reflect sunlight and clean them monthly to prevent mold in humid monsoon season.

Bird Seed Types That Work Best

Black oil sunflower seeds are the gold standard. They have high fat content, thin shells, and attract the widest variety of species. Nearly every seed-eating bird in New Mexico will eat them.

Nyjer (thistle) seed specifically targets finches Lesser Goldfinches, House Finches, and Pine Siskins. Use specialized feeders with tiny ports to prevent waste.

White proso millet attracts ground feeders like doves, towhees, sparrows, and quail. Scatter it on the ground or offer in platform feeders.

Safflower seeds have a bitter taste that squirrels and grackles usually avoid, but cardinals, chickadees, and other desirable birds eat readily.

Avoid cheap seed mixes with red milo, wheat, and filler grains. Birds throw these aside to find the good stuff, creating waste and mess. You’ll save money buying quality single-seed types.

Importance of Water Sources

This cannot be overstated: water attracts more bird species than feeders in New Mexico’s arid climate. Many insect-eating birds that ignore feeders will visit water features.

Birdbaths should be 1-2 inches deep with rough surfaces for secure footing. Change water every 2-3 days to prevent mosquito breeding and disease transmission.

Moving water is dramatically more attractive than still water. A simple dripper or fountain creates sound and visual cues that birds notice from much farther away. Even a slow drip from a jug with a pinhole works.

Multiple water sources at different heights serve different species. Ground-level basins attract quail and towhees, while elevated baths suit smaller songbirds.

Winter water is equally important. Heated birdbaths or frequent water changes during freezing weather provide critical resources when natural sources freeze solid.

Native Plants Birds Love

Desert Marigold (Baileya multiradiata) produces seeds that finches and sparrows eat while attracting insects that insect-eaters hunt.

Penstemon species provide nectar for hummingbirds and seeds for finches. They’re drought-tolerant once established and bloom prolifically.

Apache Plume (Fallugia paradoxa) offers nesting sites, insect habitat, and seeds. Its feathery seed heads are beautiful in fall.

Chamisa (Rabbitbrush) blooms in late summer when few other plants flower, providing critical nectar during migration.

Piñon Pine and Juniper produce cones and berries that feed jays, towhees, and other species. They also provide excellent nesting sites.

Cottonwood and Willow (if you have water) create riparian habitat that attracts the greatest diversity of species.

Native grasses left standing through winter provide seeds and shelter. Species like Blue Grama and Indian Ricegrass feed sparrows and quail.

The key principle: diverse native plantings create layered habitat with ground cover, shrubs, and trees that offer food, shelter, and nesting sites throughout the year.

Backyard Bird Identification Tips

Learning to identify birds quickly makes backyard watching much more rewarding. Here’s a step-by-step approach that works for beginners.

Size and Shape

Start by comparing the bird to familiar species. Is it sparrow-sized, robin-sized, or crow-sized? This immediately narrows possibilities.

Look at proportions: Is the tail long or short relative to the body? Is the bird chunky or slim? Does it have a crest or smooth head?

Bill shape tells you about diet. Thick, conical bills crack seeds (finches, sparrows). Thin, pointed bills catch insects (warblers, wrens). Curved bills probe bark or soil (thrashers, creepers).

Color Patterns

Note the most obvious colors first. Is there red, blue, or yellow? Where exactly do these colors appear?

Look for field marks distinctive patterns that separate similar species:

- Wing bars (stripes across the wing)

- Eye rings (circles around the eye)

- Eyebrow stripes (lines above the eye)

- Tail patterns (white edges, spots, or bars)

- Breast markings (streaks, spots, or solid colors)

Remember that males and females often look different, and juvenile birds may look completely unlike adults. Many field guides show these variations.

Behavior and Calls

How does the bird move? Does it hop or walk? Climb tree trunks? Hang upside-down? These behaviors narrow identification significantly.

Where is it feeding? Ground, tree trunk, foliage, or catching insects in flight? This indicates the bird’s ecological niche.

Calls and songs are often the fastest way to identify birds, especially in dense vegetation. Apps like Merlin Bird ID can identify songs from recordings.

Flock behavior provides clues. Some species are always in groups (finches, juncos) while others are solitary (thrashers, wrens).

Recommended Field Guides & Apps

Merlin Bird ID (free app) is phenomenering for beginners. It asks simple questions about size, color, and behavior, then suggests likely matches. The sound ID feature identifies songs automatically.

eBird (free app) lets you record sightings, see what others have spotted nearby, and explore bird distribution maps. It’s both a tool and a citizen science project.

Sibley Birds (paid app) offers comprehensive information with excellent illustrations showing different plumages and poses.

“Birds of New Mexico” by William H. Howe is the definitive state field guide with detailed range maps and habitat information.

“Kaufman Field Guide to Birds of North America” uses photographs instead of illustrations, which some beginners find easier for matching what they see.

Backyard Birds by New Mexico Region

New Mexico’s geography creates distinct birding regions with different species lists. Knowing your region helps focus your identification efforts.

Northern New Mexico

Elevation range: 5,500-13,000+ feet

Habitats: Ponderosa pine forests, aspen groves, mountain meadows, high desert

Signature species:

- Steller’s Jay (blue with black crest)

- Mountain Chickadee (white eyebrow)

- Pygmy Nuthatch (tiny, gray-brown)

- Western Bluebird (blue back, rusty breast)

- Broad-Tailed Hummingbird (males have trilling wings)

Northern yards often see elevation migrants—birds that breed high in summer and descend to lower elevations in winter. Dark-Eyed Juncos are the classic example, appearing at foothill feeders from October through April.

Winter brings irruptions of mountain species like Pine Siskins, Red Crossbills, and Evening Grosbeaks when cone crops fail at high elevations.

Central New Mexico (Rio Grande Valley)

Elevation range: 4,500-6,500 feet

Habitats: Cottonwood bosque, urban areas, desert grassland, foothills

Signature species:

- Curve-Billed Thrasher (desert specialist)

- Cactus Wren (largest wren, barred back)

- Ladder-Backed Woodpecker (black and white stripes)

- Greater Roadrunner (runs on ground, long tail)

- Say’s Phoebe (peachy belly, upright posture)

The Rio Grande corridor creates a green ribbon through otherwise arid landscape. Yards near the river or with mature cottonwoods attract riparian specialists like Yellow-Breasted Chats and Summer Tanagers.

Urban heat island effects in Albuquerque allow some species to overwinter that can’t survive in colder rural areas at the same latitude.

Southern New Mexico (Chihuahuan Desert)

Elevation range: 3,000-5,000 feet

Habitats: Creosote desert, mesquite grassland, desert scrub, yucca flats

Signature species:

- Pyrrhuloxia (gray cardinal with red accents)

- Scott’s Oriole (bright yellow and black)

- Verdin (tiny, yellow head)

- Black-Throated Sparrow (striking face pattern)

- Crissal Thrasher (rusty undertail)

Southern New Mexico gets Mexican species that barely reach the U.S. Lucifer Hummingbirds visit feeders in the Bootheel. Varied Buntings breed in desert canyons.

Water is absolutely critical in these regions. A reliable water source can attract 40+ species even in seemingly barren desert.

High Elevation vs Desert Species

Above 7,000 feet, expect coniferous forest birds adapted to cold: nuthatches, chickadees, jays, woodpeckers, and juncos. These birds have adaptations for finding insects in bark and eating conifer seeds.

Below 5,000 feet, desert specialists dominate: thrashers, quail, roadrunners, and verdins. These birds can handle extreme heat and find water in their food (insects, cactus fruit).

The transition zone (5,000-7,000 feet) offers the greatest diversity, with both groups present plus generalists that thrive in mixed habitats.

Common Questions About Backyard Birds In New Mexico

What are the most common backyard birds in New Mexico?

The top five most common backyard birds across New Mexico are:

- House Finch – Found statewide at all elevations, year-round

- Mourning Dove – Ubiquitous in every habitat from desert to mountains

- White-Winged Dove – Increasingly common in urban and suburban areas

- Northern Mockingbird – Present in yards with trees and shrubs

- Lesser Goldfinch – Common near water and seed feeders

Other extremely common species include Curve-Billed Thrasher (in desert areas), Dark-Eyed Junco (winter), Black-Chinned Hummingbird (summer), and Canyon Towhee (year-round in appropriate habitat).

The exact ranking varies by region and elevation, but these species appear on nearly every New Mexico backyard bird list.

What bird is unique to New Mexico backyards?

While no bird is completely unique to New Mexico, several specialty species are much easier to find here than elsewhere:

Curve-Billed Thrasher is the signature New Mexico backyard bird. Though found in Arizona and Texas, it’s most common and conspicuous in New Mexico’s urban and suburban desert areas.

Piñon Jay visits yards near piñon-juniper woodland, traveling in large, noisy flocks. They’re highly dependent on piñon pine seeds and face population declines.

Juniper Titmouse replaces the similar Tufted Titmouse found in eastern states. They’re common in yards with juniper trees.

In southern New Mexico, Pyrrhuloxia (the “desert cardinal”) visits feeders regularly, offering a special treat for birders from other regions.

How can I attract birds in dry desert areas?

Water is the single most important element for attracting birds in desert environments. A clean birdbath with fresh water changed every 2-3 days will attract more species than any feeder.

Add movement to water with a dripper, mister, or small fountain. The sound and sparkle attract birds from remarkable distances. I’ve seen yards go from 5 species to 25+ species just by adding a simple dripper.

Create shade with native trees and shrubs. Birds need cool refuges during intense afternoon heat. Even a small tree provides critical thermal relief.

Offer high-energy foods like black oil sunflower seeds, suet (in cooler months), and sugar water for hummingbirds. Desert life requires significant calories.

Plant native desert species that provide natural food and shelter. Mesquite, palo verde, ocotillo, and various cacti support insects, provide seeds, and offer nesting sites.

Avoid pesticides completely. Desert birds rely heavily on insects, especially when feeding nestlings. A chemically-treated yard is a bird desert.

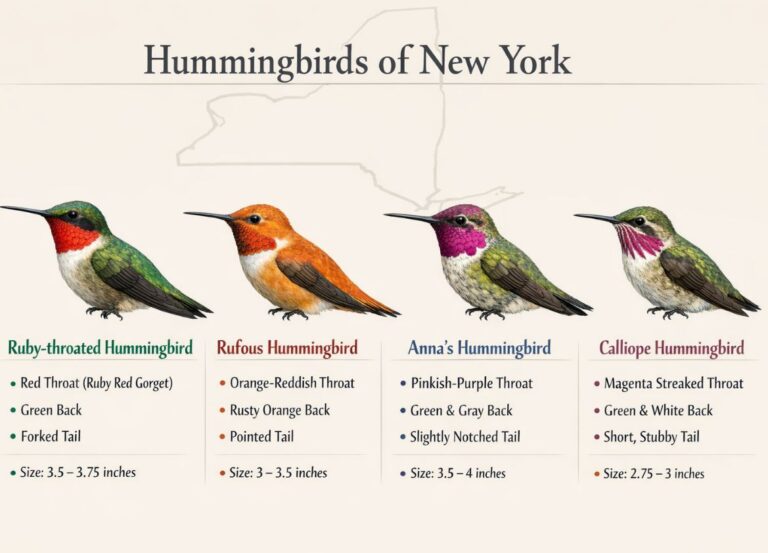

Are hummingbirds common in New Mexico backyards?

Yes! New Mexico hosts multiple hummingbird species, with Black-Chinned Hummingbirds being the most common backyard visitor statewide.

Seasonal presence: Hummingbirds arrive in April and stay through September. Peak numbers occur during fall migration (August-September) when northbound birds pass through.

Species you might see:

- Black-Chinned Hummingbird – most common, widespread

- Broad-Tailed Hummingbird – mountain areas, distinctive wing trill

- Rufous Hummingbird – aggressive migrant, fall peak

- Calliope Hummingbird – smallest, mountain migrant

- Anna’s Hummingbird – increasingly common in winter in southern NM

Feeder recipe: Mix 1 part white sugar to 4 parts water. No red dye needed—the feeder’s red parts attract them. Change every 2-3 days in hot weather.

Native plants like penstemon, salvia, trumpet vine, and desert honeysuckle provide natural nectar and are more sustainable than feeders alone.

Conservation & Protecting Backyard Birds

Your backyard can be more than entertainment—it can be genuine habitat that supports bird populations facing real challenges.

Threats Facing New Mexico Birds

Habitat loss is the primary threat. Urban sprawl, agricultural conversion, and development fragment natural areas. Riparian corridors along waterways have been reduced by over 90% since settlement.

Water scarcity intensifies with climate change and groundwater depletion. Natural water sources that birds depend on are drying up across the state.

Climate change is shifting ranges northward and upward in elevation. Some New Mexico species are losing suitable habitat as temperatures rise and precipitation patterns change.

Window collisions kill hundreds of millions of birds annually across North America. Reflective glass looks like open sky or habitat to flying birds.

Outdoor cats are estimated to kill billions of birds each year. Even well-fed pets hunt instinctively, and birds haven’t evolved defenses against this predator.

Pesticides and rodenticides poison birds directly or eliminate the insects they need to survive. Raptors and owls die from eating poisoned rodents.

How Homeowners Can Help

Keep cats indoors or create “catios” (enclosed outdoor spaces). This single action saves more birds than any other step. If your cat goes outside, use a collar with bells and keep them in during dawn and dusk when birds are most active.

Make windows visible to birds using decals, screens, or external netting. The key is breaking up reflections with patterns spaced no more than 2 inches apart.

Reduce pesticide use or eliminate it entirely. Accept some insect presence as part of a healthy ecosystem. Those “pest” insects feed baby birds.

Plant native species that provide food and shelter year-round. A yard with native plants supports 4-5 times more birds than a yard with only exotic ornamentals.

Provide clean water and keep feeders sanitary. Dirty feeders spread diseases like salmonellosis and conjunctivitis that can kill birds. Clean feeders monthly with a 10% bleach solution.

Leave dead trees (snags) standing if they’re not safety hazards. Woodpeckers excavate nest holes that dozens of other species use later.

Participate in citizen science through eBird, Project FeederWatch, or the Great Backyard Bird Count. Your observations contribute to scientific understanding of bird populations.

Ethical Bird Feeding Practices

Stop feeding if disease appears. If you see sick birds (lethargic, fluffed feathers, crusty eyes), remove feeders for 2-3 weeks and disinfect them thoroughly.

Maintain feeders year-round or not at all. Birds come to depend on reliable food sources. Starting and stopping creates stress during critical periods.

Provide appropriate foods for each season. High-fat foods in winter help birds survive cold nights. Protein-rich foods in spring support nesting.

Place feeders thoughtfully considering predator safety. Feeders should be either within 3 feet of windows (so birds can’t build fatal speed) or more than 30 feet away. Provide nearby cover but not so close that cats can ambush birds.

Don’t overcrowd feeding stations. Multiple feeders spaced apart reduce aggression and disease transmission.

Store seed properly in sealed containers away from moisture and rodents. Moldy seed can kill birds.

Conclusion

Watching Backyard Birds In New Mexico connects you to the natural rhythms of the Southwest in ways few other activities can match. From the first Black-Chinned Hummingbird arrival in April to winter flocks of juncos at your feeder, these birds bring life, color, and music to your outdoor space throughout the year.

The species you’ll see depend on your location, elevation, and habitat, but every New Mexico yard can attract birds with the right combination of food, water, and shelter. Remember that water is often more important than food in our arid climate—a simple birdbath can transform your bird list.

Start simple: put up one quality feeder with black oil sunflower seeds, add a birdbath with fresh water, and plant a few native shrubs. As you learn which species visit, you can expand your offerings to target specific birds you want to attract.

Take action today:

- Set up a basic feeding station this week

- Download the Merlin Bird ID app to identify visitors

- Join eBird to track what you see and contribute to science

- Plant one native species that provides food or shelter

- Make one window safer with decals or screens

Every small step makes your yard better habitat and helps bird populations facing real conservation challenges. The birds will reward you with daily entertainment and the satisfaction of knowing you’re making a difference.

Now grab your binoculars, fill that feeder, and see who shows up. The backyard birding community in New Mexico is welcoming and eager to help beginners. Your journey into the wonderful world of New Mexico birds starts right outside your door.