In the heart of American cities, suburbs, and farmlands, a question often arises among birdwatchers and curious observers: Why is the European Starling the most common birds in America? These glossy, speckled birds are everywhere perched on power lines, foraging in parks, and nesting in building crevices.

Yet, remarkably, they are not native to this continent at all. The European Starling (Sturnus vulgaris) was deliberately introduced to North America in the late 19th century, and within just over a century, it has become one of the most abundant bird species across the United States and Canada. Their story is one of rapid expansion, remarkable adaptability, and unintended ecological consequences that continue to shape North American ecosystems today.

Key Takeaways

- European Starlings were introduced to North America in 1890 in New York’s Central Park, with approximately 100 birds released as part of a literary enthusiast’s project.

- Their population exploded from fewer than 200 birds to over 200 million within a century, making them one of the most successful invasive species in history.

- Exceptional adaptability allows starlings to thrive in diverse habitats, from urban centers to agricultural lands, eating a wide variety of foods and nesting in numerous locations.

- Aggressive competition with native bird species for nesting cavities has led to significant declines in populations of woodpeckers, bluebirds, and other cavity-nesting birds.

- Economic and ecological impacts include millions of dollars in agricultural damage annually and disruption of native ecosystems across the continent.

Why Is The European Starlings The Most Common Birds In America

The European Starling’s dominance in America stems from several interconnected factors that created the perfect conditions for population explosion. In 1890, approximately 60 to 100 European Starlings were released in New York City’s Central Park. A second release of roughly 40 birds followed in 1891. These initial populations, numbering fewer than 200 individuals, would become the founding population for what is now estimated at over 200 million starlings across North America.

Rapid Reproduction and Population Growth

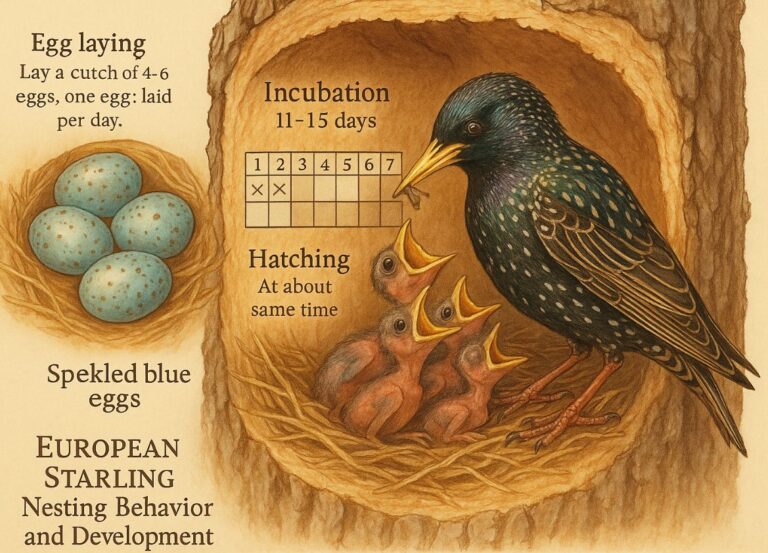

European Starlings possess extraordinarily efficient breeding capabilities. A single pair can produce two to three broods per year, with each clutch containing four to six eggs. The incubation period lasts only 12 days, and fledglings leave the nest within three weeks. This rapid reproductive cycle means that under favorable conditions, starling populations can double or triple within a single breeding season.

The species reaches sexual maturity within one year, allowing new generations to contribute to population growth almost immediately. This reproductive efficiency, combined with high survival rates in North American environments, created exponential population growth that native predators and environmental factors could not adequately control.

Dietary Flexibility and Opportunistic Feeding

One of the most significant factors contributing to the starling’s success is its remarkably flexible diet. European Starlings are true omnivores, consuming:

- Insects and invertebrates -beetles, caterpillars, grasshoppers, earthworms, and spiders during spring and summer

- Fruits and berries -cherries, grapes, apples, and various wild fruits

- Seeds and grains – wheat, corn, oats, and other agricultural crops

- Human food waste – readily available in urban and suburban environments

- Nectar and small vertebrates – occasionally supplementing their diet with diverse food sources

This dietary adaptability means starlings can survive and thrive in virtually any environment where food is available. They exploit seasonal food sources efficiently, switching between protein-rich insects during breeding season and carbohydrate-rich grains and fruits during winter months.

Environmental Adaptability and Habitat Flexibility

European Starlings demonstrate exceptional flexibility in habitat selection. Unlike many bird species that require specific environmental conditions, starlings have successfully colonized:

- Urban environments – cities and towns with abundant nesting sites in buildings and structures

- Suburban areas – residential neighborhoods with lawns, gardens, and ornamental plantings

- Agricultural lands -farms and ranches providing both food and nesting opportunities

- Grasslands and pastures – open areas ideal for foraging

- Woodland edges – transitional habitats offering diverse resources

This habitat generalist means starlings face minimal geographic or environmental barriers to expansion. They have successfully established populations from Alaska to Mexico, and from the Atlantic to the Pacific coasts.

The History of European Starlings in North America

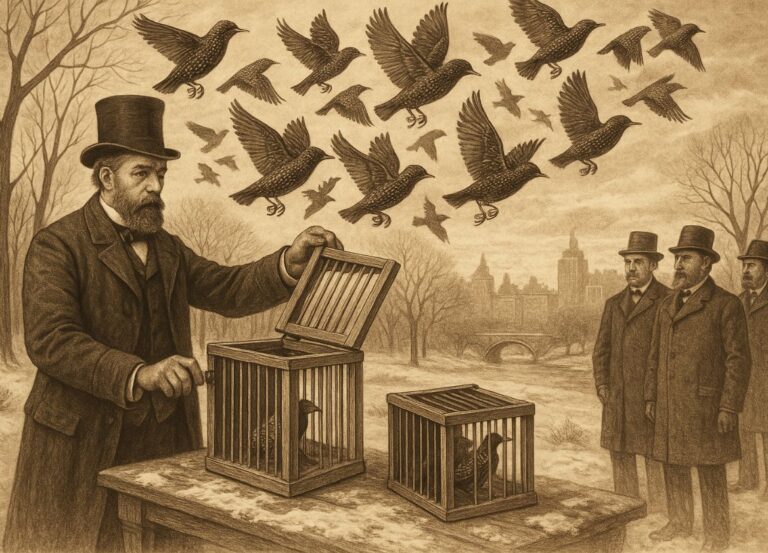

The introduction of European Starlings to North America is one of the most well-documented cases of intentional species introduction in history. The story centers on Eugene Schieffelin, a wealthy New York pharmaceutical manufacturer and member of the American Acclimatization Society in the 1870s and 1880s.

The Shakespeare Connection

According to historical accounts, Schieffelin harbored an ambitious goal: to introduce every bird species mentioned in the works of William Shakespeare to North America. The European Starling appears in Henry IV, Part 1, where the character Hotspur mentions a starling trained to repeat the name “Mortimer” to annoy King Henry IV.

In pursuit of this literary-inspired vision, Schieffelin imported European Starlings from England and released them in Central Park, New York City, in March 1890. Approximately 60 birds were released initially, followed by another 40 in 1891. Previous attempts to establish starling populations in other North American cities, including Cincinnati and Portland, had failed, but the New York population succeeded spectacularly.

Westward Expansion Across the Continent

The starlings’ spread across North America occurred with remarkable speed:

- 1890-1900: Established breeding populations in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut

- 1910s: Reached Pennsylvania, Ohio, and the Great Lakes region

- 1920s: Expanded into the Midwest, reaching Illinois, Indiana, and Michigan

- 1930s: Arrived in the Great Plains states

- 1940s: Reached the Rocky Mountains and began colonizing the West Coast

- 1950s: Established in California, Oregon, and Washington

- 1960s: Completed continental spread, reaching Alaska and northern Canada

By the 1950s, less than 70 years after their introduction, European Starlings had colonized the entire continental United States. This represents one of the fastest and most successful biological invasions in recorded history.

How European Starlings Outcompete Native Birds

The European Starling’s success has come at a significant cost to native North American bird species. Their competitive advantages have resulted in documented population declines among numerous native species.

Aggressive Nesting Behavior

European Starlings are secondary cavity nesters, meaning they do not excavate their own nesting holes but instead use cavities created by other species or natural formations. This puts them in direct competition with native cavity-nesting birds, including:

- Eastern Bluebirds (Sialia sialis)

- Tree Swallows (Tachycineta bicolor)

- Purple Martins (Progne subis)

- Various woodpecker species

- American Kestrels (Falco sparverius)

- Wood Ducks (Aix sponsa)

Starlings exhibit highly aggressive territorial behavior during nesting season. They actively evict other birds from established nests, often destroying eggs and killing nestlings in the process. Their slightly larger size and aggressive nature give them a decisive advantage in confrontations with most native cavity nesters.

Documented cases include starlings entering active bluebird nests, pecking adult birds to death, destroying eggs, and taking over the cavity. Similar aggressive takeovers have been observed with woodpecker nests, where starlings wait for woodpeckers to complete the labor-intensive excavation work before evicting them and claiming the cavity.

Superior Adaptability to Human Environments

European Starlings possess several advantages in human-modified landscapes:

- Comfort with human proximity — Starlings show minimal fear of humans, allowing them to exploit urban and suburban resources effectively

- Structural nesting flexibility — They readily nest in buildings, signs, street lights, and other artificial structures

- Tolerance of pollution and disturbance — Unlike many native species, starlings thrive despite environmental degradation

- Exploitation of agricultural resources — They efficiently utilize crops, livestock feed, and agricultural waste

These adaptations allow starlings to maintain high population densities in areas where many native species struggle or cannot survive.

Competitive Feeding Strategies

At feeding sites, starlings employ aggressive, competitive tactics:

- Flock feeding behavior — Large groups overwhelm and monopolies food sources

- Rapid consumption — Quick, efficient feeding allows them to exploit resources before competitors arrive

- Resource guarding — Aggressive defense of productive feeding areas

- Opportunistic timing — Quick response to newly available food sources

These behaviors give starlings significant advantages over native species at bird feeders, agricultural sites, and natural feeding areas.

Impact of European Starlings on U.S. Ecosystems

The ecological and economic impacts of European Starlings extend far beyond simple competition with native birds. Their presence has created cascading effects throughout North American ecosystems.

Ecological Consequences

Displacement of Native Species: Research has documented significant population declines in several native cavity-nesting species correlating with starling expansion. Eastern Bluebird populations experienced dramatic declines in the mid-20th century, partially attributed to competition with starlings for nesting sites. Conservation efforts, including installation of bluebird-specific nest boxes with entrance holes too small for starlings, have helped recovery but have not eliminated the threat.

Ecosystem Disruption: Starlings alter local ecosystems through:

- Seed dispersal of invasive plants — Starlings consume and spread seeds of non-native plant species

- Insect population impacts — While they consume pest insects, they also reduce populations of beneficial species

- Nest site monopolization — Reducing available cavities for entire communities of cavity-dependent species

- Disease transmission — Starlings can carry and transmit diseases affecting both wildlife and domestic animals

Economic Impact

The economic costs associated with European Starlings are substantial:

Agricultural Damage: Starlings cause an estimated $800 million to $1 billion annually in agricultural losses in the United States. Damage includes:

- Consumption of ripening fruits, particularly cherries, grapes, and berries

- Grain crop losses, especially corn, wheat, and sorghum

- Contamination of livestock feed at feedlots and dairy operations

- Consumption of livestock feed, with large flocks consuming significant quantities

Aviation Hazards: Starling flocks pose serious risks to aircraft. Their tendency to form large, dense flocks near airports has resulted in numerous bird strikes. The murmurations — spectacular coordinated flock movements involving thousands of birds — create particular hazards during takeoff and landing.

Infrastructure Damage: Large starling roosts cause:

- Structural damage to buildings from accumulated droppings

- Corrosion of vehicles and equipment

- Clogging of gutters and drainage systems

- Public health concerns from accumulation of fecal matter

Public Health Considerations

Starling populations, particularly large roosting flocks, present several public health concerns:

- Histoplasmosis – A fungal disease that grows in accumulated bird droppings

- Disease vectors – Starlings can carry diseases transmissible to humans and livestock

- Parasite hosts – They harbor various parasites, including mites and ticks

- Air quality – Dried fecal matter becomes airborne, creating respiratory hazards

How They Adapted to America’s Climate and Habitats

The European Starling’s extraordinary success across North America’s diverse climates and habitats demonstrates remarkable physiological and behavioral plasticity.

Climate Tolerance and Geographic Range

European Starlings have successfully established populations across an enormous climatic gradient:

Northern Adaptations: In Alaska and northern Canada, starlings endure winter temperatures below -40°F (-40°C). They survive through:

- Increased fat reserves during autumn

- Roosting in large, heat-conserving groups

- Seeking shelter in heated buildings and structures

- Fluffing feathers to create insulating air layers

Southern Adaptations: In the southern United States and Mexico, starlings cope with temperatures exceeding 100°F (38°C) through:

- Panting and gular fluttering for evaporative cooling

- Seeking shade during peak heat

- Adjusting activity patterns to cooler morning and evening hours

- Exploiting air-conditioned structures in urban areas

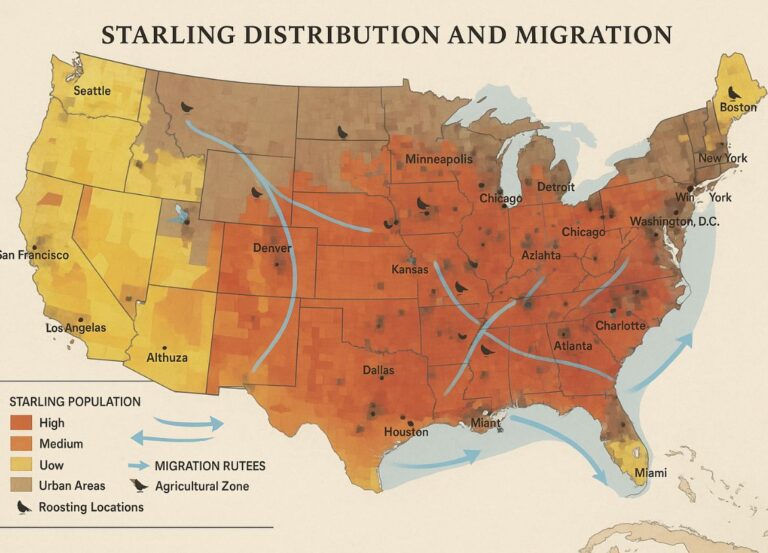

Seasonal Migration and Movement Patterns

While European Starlings are considered partial migrants, their movement patterns vary by region:

Northern Populations: Birds breeding in Canada and northern U.S. states typically migrate southward in autumn, travelling hundreds of miles to milder winter climates. They return north in early spring, often arriving before many native migrants.

Southern Populations: Starlings in temperate and southern regions often remain year-round, exhibiting only local movements in response to food availability.

Nomadic Behavior: Outside breeding season, starlings form large, mobile flocks that move in response to food resources, weather patterns, and roosting site availability.

Cognitive Abilities and Vocal Mimicry

European Starlings possess impressive cognitive capabilities that contribute to their adaptability:

Vocal Learning: Starlings are accomplished mimics, capable of reproducing:

- Songs and calls of other bird species

- Mechanical sounds (car alarms, phones, machinery)

- Human speech and whistles

- Environmental sounds from their surroundings

This vocal flexibility may provide competitive advantages in territorial defense and mate attraction.

Problem-Solving Abilities: Research has demonstrated that starlings can:

- Learn complex foraging techniques through observation

- Remember productive feeding locations across seasons

- Adapt feeding strategies based on experience

- Recognize and respond to predator threats

Social Learning: Starlings benefit from living in social groups, where individuals learn from flock mates about:

- New food sources and feeding techniques

- Predator avoidance strategies

- Optimal nesting locations

- Seasonal movement patterns

Managing the European Starling Population

Given the European Starling’s status as an invasive species with significant ecological and economic impacts, various management and control strategies have been implemented across North America.

Control Efforts and Methods

Agricultural Management: Farmers and agricultural operations employ several strategies to reduce starling damage:

- Exclusion netting — Physical barriers protecting high-value fruit crops

- Frightening devices — Propane cannons, lasers, and pyrotechnics to disperse flocks

- Habitat modification — Removing roosting sites and reducing attractants

- Taste aversive — Chemical treatments making crops unpalatable without harming birds

Nest Box Management: Conservation organizations and birdwatchers use targeted approaches:

- Entrance hole sizing — Creating openings too small for starlings (1.5 inches or less) but suitable for target native species

- Active monitoring — Removing starling nests from boxes intended for native species

- Trap boxes — Specially designed boxes that capture starlings while allowing other species to escape

Population Control Programs: Some municipalities and agricultural areas implement:

- Targeted removal — Culling programs at problematic roost sites

- Reproductive control — Egg addling or removal from accessible nests

- Roost dispersal — Systematic harassment to break up large winter roosts

Humane and Non-Lethal Approaches

Increasingly, wildlife managers emphasize non-lethal control methods:

Habitat Management: Reducing habitat suitability through:

- Sealing building entry points to prevent nesting

- Removing or modifying roosting structures

- Managing landscaping to reduce attractiveness

- Eliminating food sources near sensitive areas

Deterrent Technologies: Modern approaches include:

- Acoustic deterrents — Broadcasting distress calls or predator sounds

- Visual deterrents — Reflective tape, predator decoys, and moving objects

- Exclusion systems — Netting, wire grids, and physical barriers

- Habitat modification — Altering environments to native species

Conservation vs. Pest Control Balance

Managing European Starlings presents ethical and practical challenges:

Legal Status: Unlike native birds protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, European Starlings receive no federal protection in the United States. This allows control measures not permitted for native species, but also raises questions about humane treatment and ecological ethics.

Ecosystem Considerations: Complete eradication is neither feasible nor necessarily desirable, as:

- Starlings now occupy an ecological niche in North American ecosystems

- They provide some ecosystem services, including insect pest control

- Removal might create vacancies for other invasive species

- The ecological consequences of large-scale removal are uncertain

Integrated Management: Current best practices emphasize:

- Protecting native species through targeted interventions

- Reducing economic damage through localized control

- Accepting starling presence in areas where impacts are minimal

- Focusing resources on high-priority conservation and agricultural areas

Conclusion

The question “Why is the European Starling the most common birds in America?” has a multifaceted answer rooted in biology, history, and ecology. These remarkably adaptable birds succeeded in North America due to a perfect combination of factors: intentional introduction during a period of rapid environmental change, exceptional reproductive capacity, dietary and habitat flexibility, aggressive competitive behavior, and cognitive abilities that allowed rapid adaptation to diverse environments.

From fewer than 200 birds released in New York’s Central Park in 1890-1891, European Starlings have grown to a population exceeding 200 million individuals distributed across the entire North American continent. Their success story represents one of the most dramatic biological invasions in recorded history, with profound and lasting impacts on native ecosystems, agricultural systems, and human communities.

The European Starling’s dominance serves as a powerful reminder of the unintended consequences that can result from species introductions. What began as one person’s literary-inspired project to bring Shakespeare’s birds to America has fundamentally altered the composition of North American bird communities, displaced native species, and created ongoing economic and ecological challenges.

Will America ever control its most common bird? The answer likely lies not in elimination, which is neither feasible nor necessarily desirable, but in adaptive management that protects native species, reduces economic damage, and accepts the European Starling as a permanent, if unwelcome, member of North America’s avian community. As we move forward in 2025 and beyond, the starling’s story continues to inform conservation policy, invasive species management, and our understanding of how human actions ripple through ecosystems in ways we cannot always predict or control.